Arsène Roux Archives:

"Texte sur les dattiers à Goulmima, rédigé par un taleb local, en mai

1951"

Transliteration, retaining the author's vocalization:

"nəkni ayt məṛġad tamazirt ə-nnəġ da nəttəzraɛ iġsan ən-tiyni nəzrəɛtən agənsu-w ən-tigitin nə-yigər ig-təlla əl-fəṣṣa ig-təswa lə-fəṣṣa səwin awəd-nitni

ig-talla

adday gin tifəddaz timəzzanin ar-asənt nə-ttəbbiy tayawin adday gant xəmsa n-isəggwasən nəġəd rəbɛa arə-ttarunt

da-sətaliy kəbrayr təbuqqalt də-marəs di-ibril, han ləmnazil nnag nə-ttəkkwar tifərxin

adday təstəġ təbuqqalt nunyas ə-ttəkkwar nassəttit sə-waɛzuf ən-təsəṭṭa, han ləmnazil nnag nə-ttəkkwar tifərxin mayyu dasən-ti-nsərriy aɛzuf təg təɛanwuṭ ə-rrəkəm təɛawd imiḥ izar ə-rrəkəm ar-isəffəṭ ig awraġ ig annəqrən cəwiy tənu tiyni nbbit gə-səbɛəyyam ig a-ktubr n-asit s-anrar nə-nəqqərt g-izawiyn nləqqəḍ tənna-yənwan n-əfsər tənna ur-inwin nəɛjən tənna yənwan n-asit nə-git tizgaw n-awit əs-taddart nadərt g-ucəqquf nəkni ayt ə-ṣṣaḥra məri-yid i-tiyni qadaġ tədris ləmɛict

adday təbda təbuqqalt [added word illegible]

dats-ittəkkwar bab-ənnəs yali s-aflla-nns ar-ittini ya rəbbi səxxər tiyni lḥərma səydina muḥəmmadin

a-tizizwa mər-təssind is-immut mulay muḥəmmadin ur-təggard asəṭṭa bla tifggagin

llah allah ar-mani kə-ttawiġ a-fad digi

lɛən iblis a-yiminu awa-zzur mulay muḥəmmadin subḥan waddi yəbḍan əgənna də-wakal ad gn asəmṭal [added subscript word illegible "inu?"] gər səyyədna əɛli də-rasul əllahinu

ar-itbabba imma suləġ ggiġ kan-ujarradiy ari-tsawal sə-wawal ə-nnun a-nnəbiy muḥəmmadin allah allah ar-mani kə-ttawiġ a-fad digi

[added: nətta] ətta ɛəddan iġbula ġur ayt sidi əlġazi"

Transliteration, as I would render it (noting that, though I am from

Goulmima, I am not from Ayt Mṛġad). I added punctuation, and a few

words (in parentheses) to help, for those who need it, with readability:

"nkkni ayt mṛġad, (g) tmazirt nnġ da nttzraɛ iġsan n tiyni: nzrɛtn agnsu n tigitin

n yigr g tlla lfṣṣa, ig tswa lfṣṣa swin awd nitni

ig-talla

adday gin tifddaz timzzanin, ar-asnt nttebbiy tayawin; adday gant xmsa

n isggwasn nġd rbɛa ar-ttarunt

das (da-yas) ttaliy (g) kbrayr tbuqqalt d mars d ibril, han lemnazil

nnag nttekkwar tifrxin

adday tstġ tbuqqalt nunyas ttekkwar, nasst-it s waɛzuf n tsṭṭa, han lemnazil nnag nttekkwar tifrxin; mayyu, dasnti (da-yas-n-t) nsrriy aɛzuf tg tɛnwuṭ rrkm, tɛawd imiḥ izar rrkm ar-iseffeṭ ig awraġ ig anneqqern;

cwiy tnu tiyni nbbit g sbɛ iyyam g uktubr, nasit s anrar n-nqqert g

izawiyn nlaqqeḍ tnna ynwan nfser tnna ur inwin, nɛjn tnna ynwan nasit

ngt (g) tizgaw nawit s taddart nadert g ucqquf; nkkni ayt ṣṣḥra, mr id

i-tiyni qad aġ tdris lmɛict

adday tbda tbuqqalt [added word illegible] dats (da-t-yas) ittekkwar bab-nns yali s aflla-nns ar-ittini:

ya ṛbbi sxxer tiyni, lḥrma (n) syydna muḥmmadin

a tizizwa, mr

tssind is immut mulay muḥmmadin,

ur tggard asṭṭa bla tifggagin

llah allah ar-mani k-ttawiġ a fad

digi

lɛn iblis a yiminu, awa zzur mulay muḥmmadin,

subḥan

waddi ybḍan ignna d wakal,

ad(i) gn asmṭal [added subscript word illegible: "inu?"] gr syydna ɛli d rasul llahinu

ar-i-tbabba imma sulġ giġ kan

ujrradiy,

ar-i-tsawal s wawal nnun a nnbiy muḥmmadin

allah

allah ar-mani k-ttawiġ a fad digi

[added: ntta] ətta ɛddan iġbula ġur ayt sidi lġazi"

A bit of vocabulary:

-

the use of /zrɛ/ instead of /zzu/ which is actually more

common

-

/iġss/ n. "date pit"

-

/tafdduzt/ n. "young date palm"; pl. /tifddaz/

-

/t-ayaw-t/ n. "offshoot, sucker", also means "niece,

nephew"

-

/tabuqqalt/ n. "spathe of a palm tree containing

/ttekkwar/

-

/lemnazil/ n. pl. "seasons"

-

/ttekkwar/ n. "spadix of a palm tree", verb

/ttekkwer/: "to manually pollinate", specific to date

palm

-

/nunyas/ from v. /uny/ "to push smthg. into"; not as common as

/bbz/, /afs/

-

/taɛnwuṭ/ n. "bunch, cluster" (régime)

-

/rrkm/ n. pl. I expected /abluḥ(n)/ as the word for the first

green fruit; /rrkm/ being specific to /abluḥn/ that have fallen

off the tree and are collected to eat and as animal feed.

-

/sfeṭ/ v. "change color, in this case from green to yellow (or

red,... depending on the varietal)"

-

/anneqqer/ n. "yellow, red,... crunchy not yet ripe

date"

-

/nqqer/ v. "shake the dates off /azawiy/"

-

/azawiy/ n. "what remains of /taɛnwuṭ/ (date bunch) after it is

stripped of the fruit"

-

/acqquf/ n. "a large earthen jar with a wide mouth /zzir axatar/,

usually kept in the room where straw is stored /aḥanu n

walim/"

-

/ajrradiy/ n. "toddler, small child", rare (not in Haddachi,

Azdoud) and not sure if it is still in use today

But the high-note, literally and figuratively, of the text is its

mystical and mournful coda. Here is a relatively close-to-the-text

rendering into english:

lord god make (our) dates plentiful; (we seek) your protection, our

master Muḥmmad

bees! if you knew of lord Muḥmmad's death, you

would not weave without a loom [lit: warp beams]

god o god to where

do I take this thirst in me

my mouth, curse Iblis and start (utter

first) with my lord Muḥmmad

glory be to the one who separated the

sky and the earth

(I want them to) make me a grave between our

master Ali and the messenger of god

my mother carried me on her

back when I was still a small child

she spoke to me in your tongue

o prophet Muḥmmad

god o god to where do I take this thirst in

me

yet, many are the springs of Ayt Sidi Lġazi

It is striking that only one verse is germane to the date palm. The

rest weaves bees, thirst, mouth, language,... and the figure of the

prophet into a poetic space of deep spiritual yearning; where the

speaker's first language is not one of blood inheritance but one with

a sacred genealogy (through the mother!). The base physical words of

the "mother tongue" are somehow transmuted into hieratic speech within

the mysterious alchemy of transmission from mother to child! Does it

still sound like "berber" I wonder? Perhaps, the wrong question to

ask, as it is one of metaphysics, and spiritual lineage. The mother's

language does not even need to sound like arabic, as the latter's

spiritual essence, its breath, courses through the dull words of

"berber". A poetic reactivation of the trope: "arabic is the mother of

all languages".

Compare with al-Mukhtār Sūsi, in al-Maʕsūl (Vol. 1, p. 13),

where he also lays claim to the same hallowed language legacy, but not

through a mother's milk or an atavistic inheritance language that is

"neither fish nor fowl":

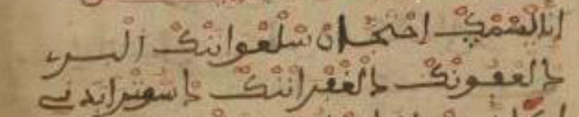

واللسان بما تتفتح له به المعاني الحلوة، لا بما يتهدج به من لغة

يرثها لا تعد من نبع ولا غرب

but through "taste", and what man elects and "finds pleasant and

beautiful to express": the men of Ilġ, according to al-Mukhtār Sūsi, moved from ʕajamah

to eloquence and an "arabness" not of a bloodline, thanks to divine

guidance, and by virtue of cultivation and of literary

craft.

</>

May 3, 2022: Updated following a tweet from @AbdellahAmennou pointing

out my mistaken transcription of certain instances of fatḥa as

/a/ and not as /ə/ (a convention of certain lmazġi scribes) in the section "transcription retaining the author's

vocalization"

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

-

Ibn Waḥšiyyah (1993). Kitāb al-Filāḥa al-Nabaṭiyya,

1st Edition (chapter devoted to nakhl, pp.

1339-1435)

-

Galand-Pernet, P. (1967).

A propos de la langue littéraire berbère du Maroc: la Koïnê des

Chleuhs. F. Steiner.

-

Cornwell, G. H., & Atia, M. (2012).

Imaginative geographies of Amazigh activism in Morocco.

Social & Cultural Geography, 13, 255–274.

-

Sūsi, al-Mukhtār (1961) al-Maʕsūl (Vol. 1)

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to moderation